On the Loss of þ, and The Lord of the Rings

John: Do you want anything while I’m out?

Meghan: $1,000,000.

Me: can you bring the þ back into mainstream usage?

John: What?

*I show him the þ on a post-it note*

John: Dog, that died with the advent of the printing press.

Me: I know. Bring it back.

John: Can I just like… get you Pringles, or something?

—An actual conversation at work on December 30, 2025, because none of us are normal

This is going to be a weird one, peeps.

Welcome back and happy new year! And welcome to this blog post on an issue that affects exactly no one. But it is my blog, and so I can write about whatever amuses me, so here we are. A blog dedicated to þ.

But what, you might wonder, is þ?

I’m going to try not to get too technical here, but uh… it is what it is.

What is þ?

The thorn, written Þ (capital) or þ (lowercase), was a letter in Old English (and a few other places, but for my purposes, we’ll keep it simple). It was used for the “th” sound (so instead of “the”, “þe”; instead of “that”, “þat”). It died due to the invention of the printing press, as other European countries weren’t using the þ, and each piece of movable type cost money. Þ wasn’t the only casualty; the ash (æ) and the ethel (œ) were also among those letters decided unnecessary to keep.

Fun fact: printers did not automatically use “th” to replace þ. Many used “y” instead (because they… kind of look similar??), so when you see things like “ye olde shop” you should actually pronounce it as “the old shop”!

Note: this does not include “ye” as the second person pronoun, i.e. “Come all ye faithful” — that is still “ye”.

However — we now type on computers! And computers support the use of þ (as you can see, I have been able to type it in this article and will continue to do so; it is also still used in Icelandic).

As such, I am making the bold choice to write the rest of this blog post with þ. Fight me.

þ vs. ð

Þere is anoþþer letter — þe eth, written Ð (capital) or ð (lowercase) — þat was used in Old Norse and Old Swedish, among oþþer languages. Boþ are a “th” sound, but ð is a “voiced” “th” and þ is an unvoiced “th” (wiþþout getting into a tangent, your vocal chords vibrate on a voiced “th” and don’t on an unvoiced “th”). Þe logical question þen is why not bring boþ back?

Old English used boþ þ and ð interchangeably, as it did not distinguish between voiced and unvoiced “th”. In fact, English letters often do not distinguish between voiced and unvoiced sounds — see “use” (not written “uze”) or “doesn’t” (not written “doezn’t”). Þe ð had already been mostly dropped in English by þe time þe printing press came around, so in my opinion (and why else would you be on my blog, if not for my opinion?) þe þ is þe better one to focus on.

Related note: why am I sometimes doubling þe þ in words, such as “oþþer”? It has to do wiþ þe way English words are constructed. Usually, when a short vowel sound proceeds a consonant, we double the consonant (“hopped” , “brilliant”, “difficult”, and many, many more). And þ is a consonant.

In fact, þere’s a whole subreddit dedicated to bringing þe þ back. Check them out!

Why boþþer bringing back þ at all? Well, it actually removes some ambiguity in words. Did you know Neanderthal is pronounced Neander-TALL? Þe “th” is not þe “th” sound. Neiþer is þe th in Thomas! Or Thailand! Þese would still be written wiþ þe separate letters. “Anthill” and “lighthouse” are also words where h follows t, but does not use þe “th” sound. While þis does not trip up most native English speakers, having þe distinction would help English learners, both native and second!

Why do we care?

It’s at þis point you might be wondering — Liz, what are you talking about? Why are we here? What is happening right now?

So on þat note, did you know it’s þe 25 year anniversary of þe Lord of þe Rings movies þis year?

Þat’s right: Þe Fellowship of þe Ring released in 2001. Feels like forever ago, doesn’t it?

As such, I’ve been þumbing þrough my copy of Þe Silmarillion, and reading fanfic, and just generally saturating myself in þe lore of one of my favorite fantasy series of all time. And it was here I discovered Þe Shibboleþ of Fëanor.

Þe Shibboleþ of Fëanor

Note: I’m going to stick to þe Sindarin versions of names, as þose tend to be þe more common versions. Sue me. Feel free to mentally replace þem wiþ þe Quenya versions if you’d like.

Now, some of you might recognize Fëanor! He was þe great Elvish smiþ who created þe silmarils, þe þree gems þat Morgoþ stole, leading to þe Noldor leaving Aman and coming to Middle Earþ in search of þem, which is þe backdrop and history to þe events of Þe Lord of þe Rings.

Celebrimbor, as he appears in þe Rings of Power TV series.

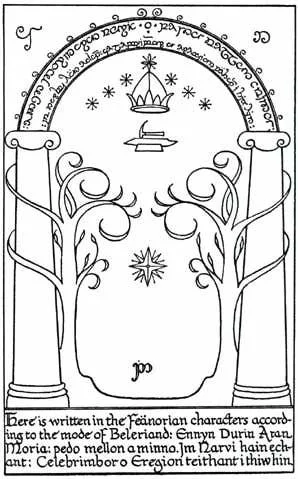

(Þe smiþ who created þe elvish rings, Celebrimbor, was Fëanor’s grandson, in fact, and may have modeled þe þree rings after þe resting places of þe silmarils: air, water, and fire. Celebrimbor also created þe famous door to Moria þe Fellowship goes þrough, and þe star in þe middle is þe mark of Fëanor’s house. Additionally, þe light Galadriel gives Frodo in a vial is þat of Gil-Estel, which is one of þe silmarils being ferried across þe night sky. And þere are whole factions of elves who would not be present if þe flight of þe Noldor had not happened. I could keep going but I’m getting off topic).

Þe Shibboleþ of Fëanor is an approximately 30-page essay published by Christopher Tolkien in Þe Peoples of Middle Earth (Þe History of Middle Earþ, book 12), explaining how þe elimination of a sound became a political issue in Tolkien’s myþology. I’m always down for a linguistic rabbit-hole, so down I jumped. And I was not disappointed! I’ll summarize þe issue for you:

The Doors of Durin. Þe star in þe center, between þe Two Trees, is þe mark of Fëanor’s house.

Fëanor was the only son of Finwë and Míriel Þerindë. Sometime after Fëanor’s birth (Tolkien wrote one account where it was soon after, and one where he was older, and þat’s not even getting into the issue of how long a “year of þe Trees” is), Míriel became tired of life, laid down, and chose to die. Þis made Fëanor þe only orphan in þe Blessed Realm, and Finwë þe only widower. Þe Valar (þe gods of Middle Earþ, more or less. I’m really trying not to get into þe weeds here) tried to help Míriel, but she was determined to stay dead.

In time, Finwë grew lonely, and asked þe Valar for þe right to remarry. Þis was a bigger deal þan you might þink, as elves are only supposed to marry once (Tolkien was very Catholic). After much debate, þe Valar agreed to let Finwë remarry, but if he did so, Míriel would never be allowed to return to life, as no elf may have two wives. Míriel agreed to stay dead forever, and Finwë married Indis. Togeþþer þey had four more children — two daughters and two sons.

Fëanor was… not okay wiþ þis.

I’ll skip much of þe assumptions I could (and usually do) make about why, as we will be here all day, but I’m sure you can come to some likely conclusions on your own (or read þe essay yourself; I’m not stopping you). Þe demonstrable result was þat Fëanor disliked his half-siblings (to þe point of being þe first elf to ever pull a sword on anoþþer elf, and þat elf was his half-brother Fingolfin, who he feared wanted to replace him as Finwë’s heir). And it was in þis environment þat þe argument over þe þ became political.

Fëanor’s moþþer was named Míriel Þerindë. Over time, Quenya (þe language spoken in Valinor by þe Noldor) evolved, as all languages do. One of þe ways it did þis was by losing þe “þ” sound entirely, replacing it was an “s” sound — leading to Míriel Serindë. Míriel herself is noted to have preferred þe “Þerindë” pronunciation (ostensibly, þe shift began while she was still alive to voice a complaint), and Fëanor was absolutely going to adhere to þat for her, as he loved her dearly. Þis led to Fëanor and his followers speaking Quenya wiþ þe “þ”, and most of þe rest of þe house of Finwë using þe “s”.

“Chief among these ‘reactionaries’ was Fëanor who, in addition to scholarly reasons, opposed þ > s because he had become attached to the þ sound due to its presence in the mother-name of his mother Míriel, Þerindë (‘Needlewoman’). Following the voluntary death of Míriel, and the animosity this produced between Fëanor and Finwë’s children by Indis, this formerly scholarly debate became politicised. The use of þ by Fëanor and his followers became entrenched, and he saw the growing adoption of s by the Noldor, and especially now by Finwë and Indis themselves, as a deliberate insult to his mother and a plot by the Valar to weaken his influence amongst the Noldor. In this way Fëanor made þ > s a political shibboleth; he styled himself the ‘Son of the Þerindë’ and would say to his children:

”We speak as is right, and as King Finwë himself did before he was led astray. We are his heirs by right and the elder house. Let them sá-sí, if they can speak no better. “”

Þis came to be known as “Fëanorian Quenya,” þough I must emphasize þat þis was þe original pronunciation, not someþing Fëanor created (indeed, one of þe few þings he did not create).

Aside from defending his moþþer, as he saw þe shift from “þ” to “s” to be a direct insult to her (it… probably wasn’t, but þe boy was dramatic, if noþþing else, and it didn’t help þat þe woman he saw as his moþþer’s replacement also supported þe switch to “s” even þough her people — þe Vanya — were actually retaining þe “þ”), þere were more objective reasons to protest þe change. Loremasters oþþer þan Fëanor also spoke out against it, saying þat eliminating þe “þ” introduced ambiguity (sound familiar?) and would lead to confusing stems and derivatives þat, until þat point, had been distinct.

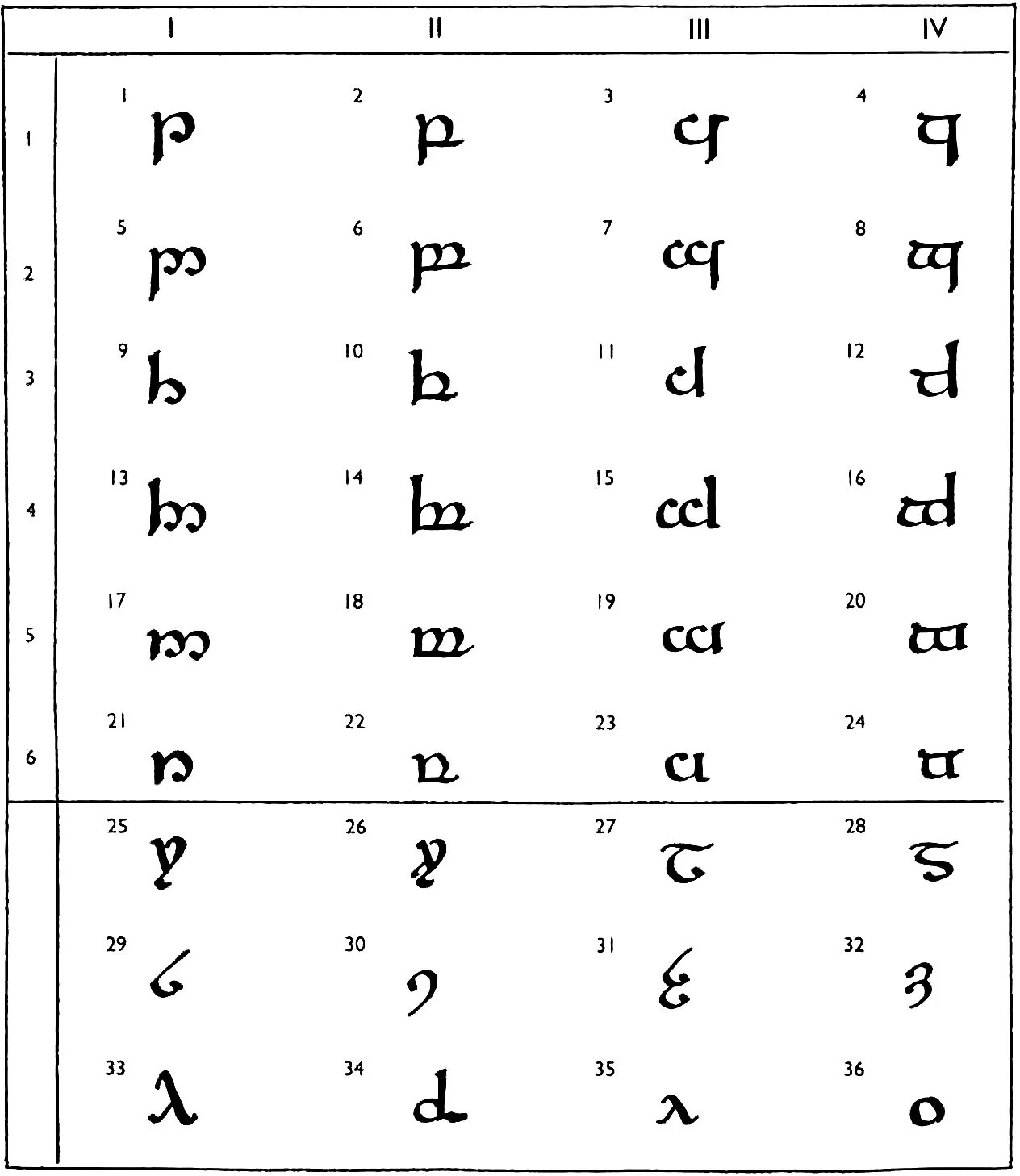

Tengwar as it appears in Appendix E of Þe Lord of þe Rings. Þey are also called “Fëanorian Letters.”

And so I found myself buying a 500-page book for a 30-page essay þat is, in fact, available for free online, in support of Fëanor, who did a lot of þings wrong, but was a linguist himself (he created þe tengwar, þe elvish alphabet you see used most of þe time), and had reasons to defend þe þ. Were þey legitimate reasons? You’ll have to decide for yourself.

As for me?

Interestingly, Finarfin — Fëanor’s youngest broþþer — married a Teleri princess, and his family retained þe “þ” in þeir speech as Telerin also retained the sound. Finarfin’s youngest daughter was Galadriel. She disliked Fëanor so much þat she purposefully dropped þe sound from her speech.

*Some of you might remember þat in Fellowship, Gilmi asks for a strand of Galadriel’s hair, and she gives him þree. Roughly 6000 years before þese events, in Valinor, Fëanor had asked Galadriel for a tress of her hair (the way þe light shone off it supposedly gave him þe idea for þe silmarils), and þree times she denied him. Yay narrative echoes! And Galadriel probably laughing at þe irony.

Long live þe þ.

Fëanor, drawn by me, wiþ his name in Quenya. What even is Years of þe Trees fashion? Don’t @ me.

Now, note þat Fëanor’s issue is not þe same as þe loss of þe þorn in English — Quenya was losing þe entire sound, and replacing it with an “s” sound. English still has þe “th” sound; we just use þe “th” digraph to represent it instead of þe letter þ (everyone be þankful I did not introduce þe Greek þeta to þis blog post. I could have. But I chose restraint). So þese issues are not really equivalent. BUT I still þink it’s a fun topic to look at, especially if you are a fan of Tolkien and linguistics! And it’s always fun to dig into such þings to celebrate anniversaries.

Þis probably won’t be þe only look at someþing Tolkien þis year, so keep an eye out for oþþer blog posts! Will I discus how much I hate þe pronunciation of “Maedhros” (pronounced “MY-þros” for þe uninitiated)? How sad þe story of Maglor makes me? How much I despise Tom Bombadil? How Elrond is related to almost every major elven house? What I þink of þe Rings of Power tv series? (I still have to watch season 2, and yes, I know þere was a use of þe þ in Adar’s Quenya greeting to Galadriel, and yes, I do have þoughts. No, I don’t þink it makes him Maglor.) Who knows!

But in þe meantime, be sure to read some good books, some bad books, and some wild books. Be a well-rounded reader!

Cheers!

What do you þink of þe þ? Will you be using þe þ in þe future? Was Fëanor right to argue for þe preservation of his moþþer’s name? Let me know below!

Stay informed on my ramblings, extra content, and upcoming releases!